|

[I was asked to contribute two-hundred words to a literary journal's blog on the subject of "books and nostalgia." I composed this piece in response, but as a result of its growing to this size, they unsurprisingly declined to publish it.]

Autopsy of an Inscription, 2/9/88

I must admit I don't have a nostalgic connection to any particular book. Perhaps my closest equivalent is a desire not to have read a particular book, so that all its revelations and reversals would seem as fresh to me now as upon first reading. But like anyone who collects books, I have a great many dead people's objects in my apartment, probably many more than I even realise, and there are times, when I come upon some especially revealing inscription, or ex libris, or -- prize of prizes, a personal memento, such as a letter -- that I feel myself at risk of becoming superstitious.

I feel, in other words, the possibility that the object in my hands is haunted (I am even sometimes, such as right now, in the mood to indulge this feeling), and that if I don't close the book immediately, and turn on a basketball game, or text a friend, or contemplate the apple on my neighbour's tree that for some reason he refuses pick, and that will probably rot on the branch--if I don't do one of these things, then the ghost of the book's suddenly apparent former owner will force its way into my imagination, and thereby insist I carry it back into life. I feel, in other words, that these dead people are nostalgic for living, and that precisely because I'm not nostalgic, I'm an ideal vessel for them to live inside again. Fortunately for me, I am a rational and scientific person.

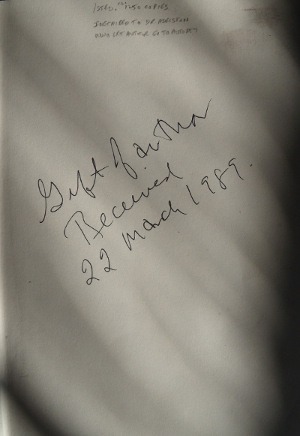

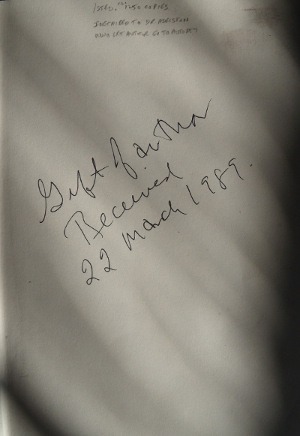

Because I'm in the mood, however, I will write about Dr. Lester Adelson, one of the more vivid ghosts in my library. He is housed in a first edition copy of The Rainbow Stories (1989) by William T. Vollmann. According to an ungainly note scrawled on the first page, this copy was a "Gift of author / Received / 22 March 1989," above which another note, penciled in by the bookseller from whom I purchased the volume, says it is "INSCRIBED TO DR. ADELSTON [sic] / WHO LET AUTHOR GO TO AUTOPSY."

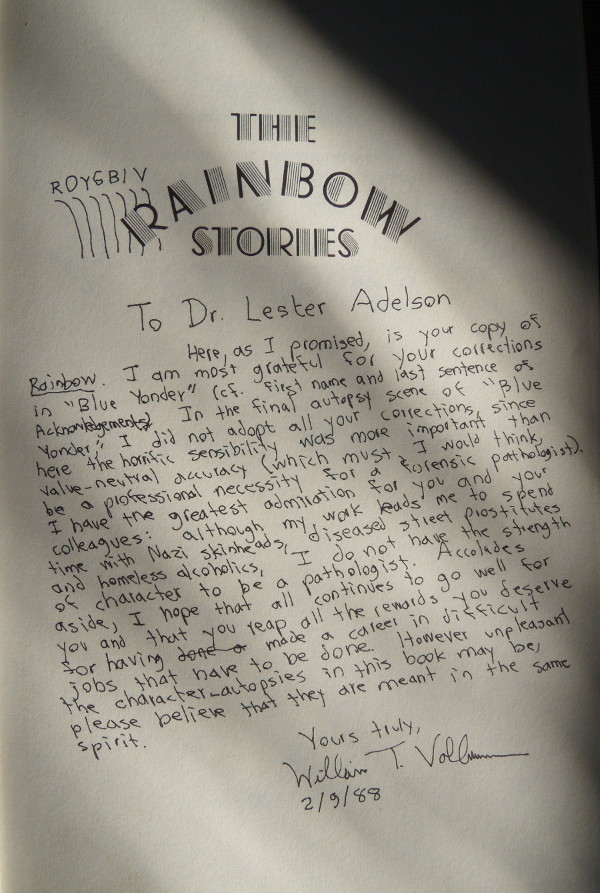

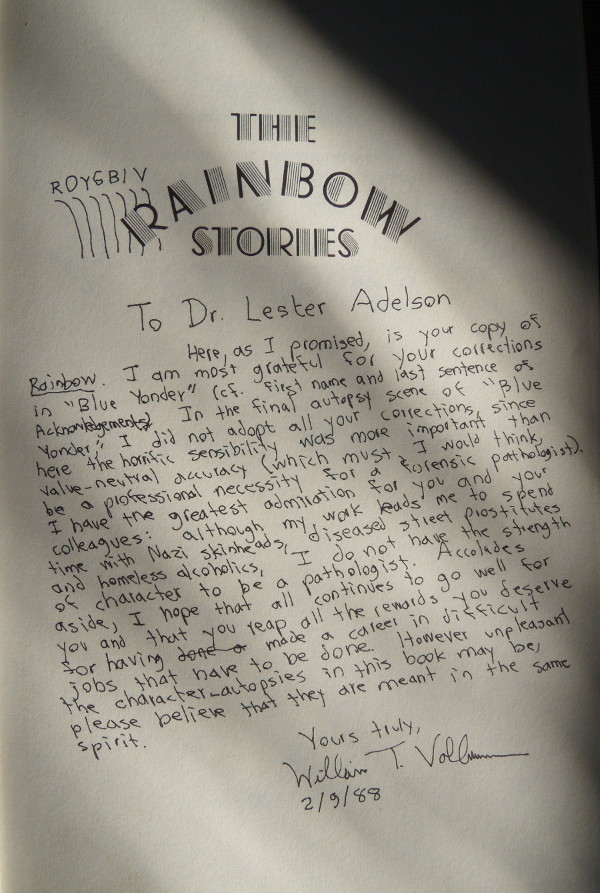

More remarkable is the title page inscription, which reveals that Dr. Adelson edited a draft of the story "Blue Yonder," though Vollmann didn't incorporate all his corrections ("here the horrific sensibility was more important than value-neutral accuracy," he writes). Vollmann was evidently impressed by the elder doctor: "although my work leads me to spend time with Nazi skinheads, diseased street prostitutes and homeless alcoholics, I do not have the strength of character to be a pathologist." If the book was received on the 22nd of March, it must have been mailed, or only much later handed over, as Vollmann dates the inscription 2/9/88.

This seems like a simple enough transaction, but something curious happens when one refers to the book's acknowledgements. Here, Vollmann extends thanks to all those who assisted "in showing me the colours of the RAINBOW," and the list begins with Dr. Lester Adelson, whose book, Pathology of Homicide (according to Michael Hemmingson's William T. Vollmann: An Annotated Bibliography), Vollmann used throughout the composition of The Rainbow Stories. But after this typical catalogue of acknowledgments, there comes a second, smaller paragraph: "Above all I would like to thank those persons unnamed or unattributed here," among whom is "the doctor who let me see my first autopsy."

I wish I'd noticed this detail when I purchased the book. I would have asked the seller (whose name I've forgotten; he was with a travelling antiquarian fair) how he knew that Dr. Adelson was the one who let Vollmann "GO TO AUTOPSY," as he so confidently penciled in, when Vollmann's inscription only credits Adelson for correcting the details of "Blue Yonder." I'm tempted to consider them two different doctors -- the anonymous doctor, who let Vollmann observe; and Dr. Adelson, who corrected the story -- but then why would the seller have invented this information? Why would he have connected a phrase at the very end of an enormous and largely confusing book to the inscription? Isn't it more likely that whoever sold him the book told him this little bit of gossip? Did they invent it? And why? The most intriguing version of events -- and therefore the one I am most likely to adopt -- is that Adelson was the doctor who illicitly allowed Vollmann to observe the autopsy, and though Vollmann claims not to attribute him, in fact Adelson is hiding in plain sight.

Because I frequently get that haunted sensation when I contemplate this book (I read The Rainbow Stories in a new, soulless paperback), there is only so far I desire to go into the life of Dr. Lester Adelson -- that is, there is only so far I desire his life to come into mine. Nevertheless I can't help myself, and have learned a good deal.

Dr. Lester Adelson served as Chief Deputy Coroner of Cuyahoga County, which has its seat in Cleveland, Ohio. He came to prominence during the 1954 trial of Dr. Sam Sheppard, one of the many trials that rose to a sufficient level of popular voyeurism to be deemed "The Trial of the Century." Dr. Sheppard was accused of murdering his wife, Marilyn Sheppard, who was pregnant at the time, by bludgeoning her to death. After a controversial trial, the jury found him guilty of second-degree murder, a verdict that caused his mother to commit suicide (and his father died eleven days later). Following a decade of imprisonment, an appeal eventually ended in acquittal. Sheppard, who maintained his innocence to the last, died of liver failure in 1970 after spending a year as a professional wrestler, "Killer" Sam Sheppard. His story, minus the bit about wrestling, and plus a relatively happy ending, is said to have inspired the Harrison Ford movie The Fugitive (1993).

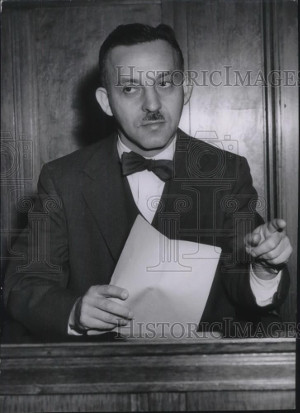

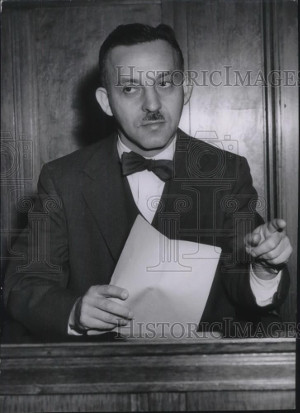

Dr. Adelson served as the prosecution's first witness. It was his task to establish that Marilyn Sheppard had died a violent death. Over the course of two days, he displayed autopsy slides so gruesome that Sheppard asked permission to leave the courtroom (he was denied). In this photo, Adelson is seen on the witness stand, pointing a finger though not making eye contact with whomever, or whatever, he's pointing to. (The image comes with an ugly watermark, because the original is for purchase on eBay for US$27.00.)

In 1999, Dr. Sheppard's son sued Cuyahoga County for his father's wrongful imprisonment. During this suit, of which I've never learned the outcome, Marilyn's body, and that of her unborn son, were exhumed. Shockingly, certain details -- that the fetus had been autopsied, for instance, though no autopsy report existed -- raised questions about whether the coroner's office had concealed evidence all those years ago. As far as I know, this suspicion has never been confirmed one way or another, and certainly nothing useful can be gained by examining the rather smug expression of Adelson in this photo, crisscrossed with watermarks. (It occurs to me that, if the Cuyahoga County coroner's office was indeed concealing evidence, then sneaking Vollmann in to observe an autopsy is all too typical of a poorly managed, even malicious institution, and not the unique event I've always imagined.)

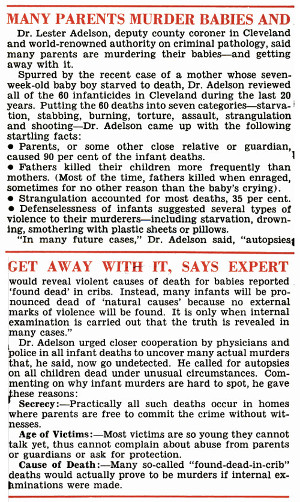

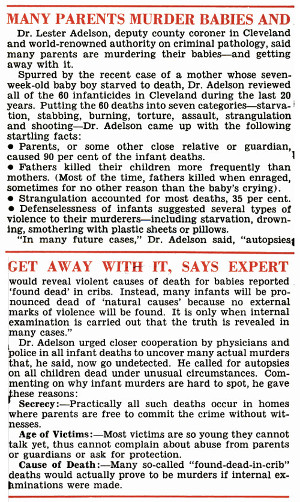

The trial brought Adelson to wider attention, and for many years his comment was sought on various crimes. A May 1963 article in Jet, "The Weekly Negro News Magazine," illustrates the minor, back-page fame Adelson enjoyed during this time. Under the sensational headline "MANY PARENTS MURDER BABIES AND GET AWAY WITH IT, SAYS EXPERT," Adelson is billed as a "world-renowned authority on criminal pathology." Perhaps importantly, he calls for autopsies "on all children dead under unusual circumstances."

Despite the rumours emerging from the Sheppard trial -- a trial, it seems, from which no one's reputation escaped without tarnish -- Dr. Adelson appears to be remembered as an ethical and estimable member of his profession, for which Vollmann lacks the strength of character. According to the Dittrick Medical History Center, which stores Adelson's papers in seventeen boxes (though not the material related to the Sheppard case), Adelson showed "outspoken support of gun control and tough child abuse laws."

The mystery of whether Vollmann observed the autopsy with Dr. Lester Adelson remains. Regardless, when I read the inscription, or hold The Rainbow Stories in my hands -- in fact, when I simply see its spine on the shelf, and am reminded of it -- I envision a young Vollmann and an old Adelson, the prolific emerging writer and the storied, perhaps secretive pathologist, keenly observing the dissection of a corpse. Perhaps the horrific sensibility is more important than value-neutral accuracy, because I smell formaldehyde, and see the cold, diagnostic light of the room, and the silver scalpel, and it might seem, in this moment, that I'm being drawn backward in time. But in reality -- that is, in my imagination -- it's the memory of this peculiar moment, a memory housed in this particular book and nowhere else, that is drawing forward, toward me. It insists upon being remembered as if it were true, and at certain times -- such as for the last hour, as I've written this -- I admit I'm vulnerable to such a ghost. I admit I'm likely to be inhabited by someone like Dr. Lester Adelson. But then, being a rational, scientific person, who under no circumstances will catch himself acting on superstition, I sensibly close this notebook and return to my own life.

|